B-Side #2: Growing Pains - Marupo’s Commercial Kitchen

Red Tape, Red Tape Everywhere

Greetings, it’s Marupo here. Thanks for joining us on another entry on B-Sides. This time, we’ll be tackling a heftier topic, namely Marupo’s journey thus far in trying to expand from a humble home-chef to a commercial food and beverage establishment in Michigan. We’ll delve into some of the subtle hurdles in “becoming official”, the struggles we faced, as well as gradual growth and mindset shifts we develop as a business. Given these experiences are prevalent among most entrepreneurs trying to scale their business, I found it appropriate to name this series “Growing Pains”.

To make it easier for me to distill the past - almost 2 years - of experiences, I have decided to break it into several parts.

Here’s an outline below (this will be updated with links as new posts are created):

[This post] The Red Tapes we faced and our journey to our first commercial kitchen: Growing Hope

[Coming next] Our migration to Washtenaw Food Hub and Q Bakehouse and the struggles + lessons learned on the way

With that said, let's dive into the first major hurdle for most food entrepreneurs - commercial kitchens.

Tripping over red tape as we start

Learning how to sell at farmers markets

Back in Fall 2022, after a long self-reflection on my life journey thus far (thanks Covid) I decided to take the leap and sell egg tarts at the Ann Arbor Farmers Market. In my naivety, I thought it’d be as simple as walking up to the market manager and asking when I could show up. As they tried to stay respectful (I’m guessing this happens a lot in their line of work), I was asked the following questions:

What are you trying to sell? Does it fall under cottage food law?

Where do you operate out of? Do you have a kitchen license?

Who in your team is certified, do you have a ServSafe?

Almost instantly, I knew I was way over my head. As I tried to decipher what they asked, I was handed a multi-page application form to go through on my own time, and stepped aside so they could help the next customer.

Once I got home, I researched Michigan’s Cottage Food Policy. In summary, if the food you’re making is considered low risk and shelf-stable, you can operate out of home without needing to go through the lengthy licensing, registration or inspection process (costing approx $500/yr + a month of processing time).

“I see! That’s how all the home-bakers do it” I told myself. Feeling reassured that my egg tart was considered a baked good, I went back to the market manager and told her I qualify under cottage food…

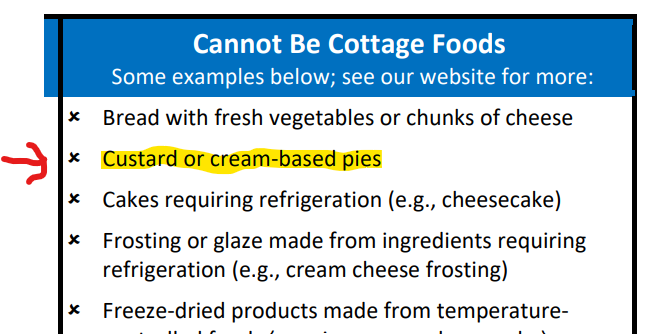

Upon which she pointed at this line in the policy.

… followed by a theoretical discussion on exactly what an egg tart is. It’s true that egg tarts are baked in the oven at over 350°F… yet unlike your typical “cookies” or “brownies” that the locals are accustomed to, egg tarts can be considered something foreign for local health inspectors. The closest equivalent are lemon/lime tarts or the french Tarte aux fruits frais, both of which do have “custard” requiring refrigeration. In the absence of an official food lab test (~$300 + 1 month of continuous sample deliveries), my claims that egg tarts are “low risk” were flimsy at best. Thus I took another step back in my plan… and prepared myself for the arduous path of commercial kitchen licensing.

The nuances of commercial licensing

At this point you might ask: why not just use an existing commercial kitchen, instead of licensing your own? Though it may sound like a no-brainer at first, the “commercial licensing” process actually comes in three-folds of requirements.

[$???] The kitchen as a facility has to be up-to-code and approved by the authorities

Proper electric output and appropriate equipments for the space

Water heating capacity

Fire safe code

And much more

[$500 /yr] The operating business (i.e. Marupo Eats as a legal entity in this case), has to be inspected and their operating procedures approved

How you store your ingredients

How you prevent food contamination including procedure to deal with sick employees

How you temperature control your food so they don’t spoil

[$180 / 5 yrs] The managing supervisor (i.e. Marupo/Bennett) need to be certified in food safety and food service practices. One of the most well-known certifiers being ServSafe.

What temperature do you have to cook each type of meat up to?

What are the safe temperature ranges for hot/cold holding your products?

How to identify and protect against food-borne illnesses?

To make things even more complex… there are 2 different government authorities that process licensing:

Your County’s Health Department (Marupo uses Washtenaw County’s) as well as

Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (i.e. MDARD aka “the state” inspector).

The guidelines for when to go through which authority is vague, but from my understanding, if you’re primarily selling to retail customers… you go through your county, whereas if you’re wholesaling to other businesses or “established enough” you go with MDARD.

So going back to my rhetorical question above, using an existing commercial kitchen is almost a given for a new food entrepreneur, but that only addresses 1 out of the 3 requirements needed to be considered “commercially licensed”. With that context, let's take a look at Marupo’s personal experience on looking for our commercial kitchen.

What “is” a commercial kitchen?:

Ghost Kitchens and Commissary Kitchens

Looking at Ghost Kitchen-ing

My initial approach was to go the “ghost kitchen” route. For those unfamiliar with the concept, you essentially operate out of an existing restaurants’ kitchen but focus on online and virtual sales. Given the abundance of bars and brunch restaurants around the area, I figured offering to help chip in towards their rent cost during their off time would be a welcomed proposal…

… that is until I actually reached out to several restaurant owners and pitched my idea. Here are some of their candid responses:

“We don’t do these types of arrangements, since it’s just not worth the risk.”

“How do I know you and your crew won’t leave a mess after your evening shift? When my team comes in early-morning our schedule is tight. If we open late because we have to spend an hour cleaning up your messes, that can be hundreds if not thousands of dollars lost, not to mentioned disappointed customers and a hit against our own reputation”

“There’s the risk of liability too. While you seem like a fair and decent guy, we're skeptical of partnering with someone new to the food business. After all, if there’s any report of food poisoning, our kitchen also has to go through rounds of re-inspection and worst case might get shut down.”

That’s when it clicked for me: a commercial kitchen is more than just a place to “stamp” the food you make as commercial-grade. It is THE beating heart of any food restaurant. In hindsight, it was obvious why any restaurant owner would be hesitant to expose this metaphorical heart to vulnerability, least of all to a random cold caller with no official culinary education at all!

Ahem:

As I was visually dejected and ready to leave the diner, the owner followed up with this:

“Look, I like seeing passionate young ones get into the industry. Sharing with us ain’t happening, but have you looked at commissary kitchens?”

No… no I haven’t. In fact I haven’t even heard of the term before then. Thankfully, this side comment helped steer me in the right direction; commissary kitchens are dedicated commercial kitchens that are intended for shared use. After searching for a few options in my vicinity, I eventually selected our first kitchen candidate: The Growing Hope Incubator Kitchen in Ypsilanti.

Growing Hope: Our first commissary kitchen

By the time we finally got approval from the county to operate, several months had passed and we’re now in Feb 2023. Despite the slight setback in timeline, being a part of the Growing Hope community turned out to be a massive boon for us as we started out. The “makers” there consisted of businesses at different stages of maturity; from those that are starting out just like Marupo, to others who have been at it for several years, boasting products in multiple storefronts or even wholesale clients. Having these entrepreneurs who shared our passion for starting their own food business and joined this incubator kitchen of their own volition served as a continuous source of inspiration and motivation for us to push forward.

Yet despite these blessings, sharing kitchen space inherently comes with its own challenges, first of which stems from the obvious fact that there are restrictions on when the space is available. The typical kitchen work hours (6AM - 6PM) are usually occupied by the long-standing tenants. Fledgling entrepreneurs like Marupo might initially brush this off by saying “I’ll just work the evenings / night-owl hours”, but as we continued to scale, the impact of this limitation manifests itself in other ways…For starters, operating outside regular business hours means significantly slower sales traffic through on-demand delivery apps. Moreover, the fact that our shifts were always in the evening unwittingly deterred candidates who desire a full-time work shift with regular hours. This ended up with our initial crew consisting heavily of people looking for temporary part-time gigs for side-income (like students over the summer), which then led to inevitable turnover and a need to retrain employees repetitively.

Besides the work hours, another challenge was the inability to control delays in rental start time. While every maker has good intentions, an unfortunate kitchen mishap in the morning could result in a snowball effect of delays for subsequent renters the rest of the day. By the time we arrived at the kitchen at night, this would result in idle staff waiting (sometimes upward of an hour) for their shift to start, knowing they will now either have less time to do their tasks or have to leave later than they’re scheduled to get things done. Worst still, we would run the risk of missing customer orders, which would obviously be followed by subpar customer reviews.

Lastly, there was the inflexibility of equipment choice. Being a shared kitchen intended to serve a variety of food businesses, the owner has to strike a balance between having versatile equipment versus specialized ones. In Marupo’s case, this meant working with a generic convection oven used for both savory and sweet baking in contrast to bakers’ ovens. More specifically, the oven at Growing Hope featured a single temperature, as opposed to selecting a precise top and separate bottom temperature range. It also did not allow chefs to adjust the internal fan speed. These seemingly minute differences are particularly constraining for egg tarts, where you want the bottom heat to be high to cook the crust quickly to prevent shrinkage, while keeping the top temperature lower so the custard stays tame (and doesn’t turn into scrambled eggs).

With that being said, while Marupo continued to use Growing Hope as our current kitchen, we passively looked for a back-up kitchen as insurance. After all, there was always a risk that we wouldn’t get the time slots we requested and the slots we did secure thus far were rather limited (3 hours on Thursday nights and 2 on Fridays). Around that time, while we found our footing at the Ann Arbor Farmers Market, we also befriended quite a few other vendors. As we spent 8+ hrs together on market days, many vendors often chatted with each other, giving us the chance to send pulses out and see where other prepared food providers operated out of. It was on one of those unassuming days that we’d eventually learn about what would become the next step in our commercial kitchen journey: The Washtenaw Food Hub (and Q Bakehouse)

…Continue reading in our next post (we’ll link it when it’s out :) )